United Nations Development Programme, “Journey to Extremism in Africa: Pathways to Recruitment and Disengagement,” February 2023. This is a follow-up to an impactful and insightful 2017 study that focused on state abuses as a “tipping point” for recruitment. This follow-on report makes a key distinction between recruits who join, often quite quickly, due to a trigger event, versus “slow” recruits who do not have a single trigger event. There’s a lot to think about here.

Rahmane Idrissa, “In Bamako,” London Review of Books, 2 February 2023. Prof. Idrissa is essential reading on the Sahel, although I paused over almost every sentence in the below paragraph – I don’t agree with the implication that Dicko had or has a master plan.

Doumbi’s talk of ‘wars of religion’ tells us something about the clashing visions that could easily destroy Hampâté Bâ’s multicultural vision of Mali. Doumbi’s main adversary is Imam Mahmoud Dicko, a charismatic Salafi cleric who has been working for decades to turn Mali into an Islamic republic. He was instrumental in Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta’s accession to the presidency in 2013: in return for Dicko’s support, Keïta promised to promote an Islamist platform championed by the youth wing of Dicko’s unofficial movement. But Keïta didn’t come good, and in the summer of 2020, Dicko helped to engineer his downfall. Until the military takeover later that year, Dicko could almost smell the ultimate prize – a constitutional change that would turn his informal position as Mali’s ‘moral authority’ (a label given to him by the media) into an official one in an Islamised or even fully Islamic republic. That would have brought jihadist leaders into the political process, and driven Doumbi, and others like him, into the wilderness.

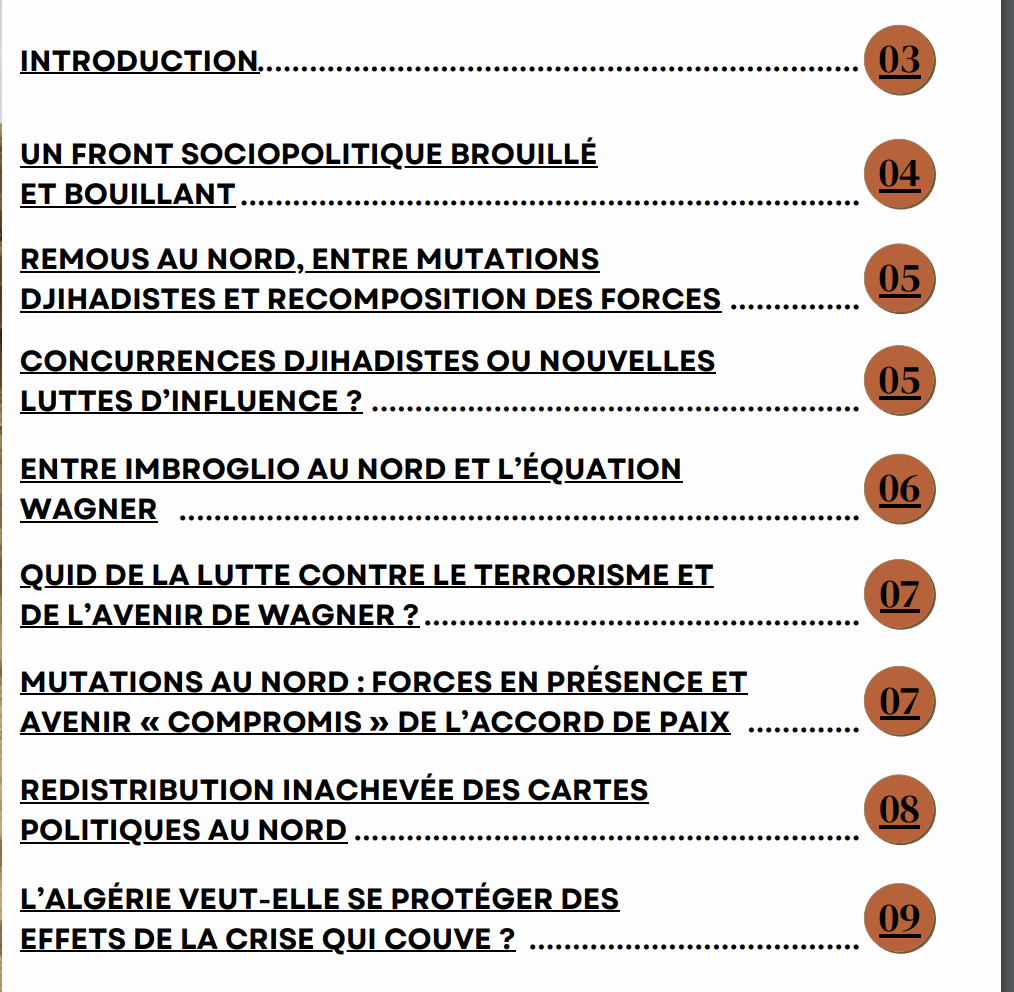

Timbuktu Institute, “Mali: Évolutions de la transition et nouvelles dynamiques sociopolitiques et sécuritaires au nord,” January 2023. Here’s the table of contents:

Kalidou Sy, “Le désarroi de Youssouf, le policier qui failli arrêter Malam Dicko,” afriqueXXI, 6 January 2023. Amazing details here:

À Djibo, le rapport à la religion a toujours été mesuré. Différents courants de l’islam cohabitaient. « Il y avait deux confréries : la Tidjaniya (les Doucouré) et la mosquée de Woursababé (les Cissé). Ces derniers furent les premiers à s’être installés à Djibo. » Mais au début des années 1990, l’arrivée d’un homme a tout changé : « C’était en 1991 ou en 1992, je ne sais plus. Le père de Malam Dicko est arrivé d’un village malien situé à la frontière du Burkina. »

Il commence par demander une parcelle de terre pour construire sa mosquée – requête qui est acceptée par les Tidjanes et les Woursababés. Avec ses discours « révolutionnaires », il cherche à déconstruire l’ordre social et n’hésite pas à s’en prendre ouvertement à ses pairs marabouts. « Dans ses prêches, il soutient qu’un marabout ne doit pas attendre d’aumône, qu’il doit travailler lui-même, qu’il ne faut pas faire de mariages fastueux avec de grosses dépenses pour ensuite vivre dans la précarité », explique Youssouf. Cela ne plaît guère aux autres confréries, d’autant qu’au fil du temps, le nombre de ses adeptes a augmenté.

Au début des années 2010, son fils Ibrahim Malam Dicko a pris la relève. Très éloquent, il était vu comme un gourou par ses adeptes : « Il prêchait du social, se remémore Youssouf. Malam disait qu’il n’est pas permis d’égorger plus de deux moutons durant les fêtes. Il avait beaucoup d’adeptes qui voyaient en ses discours une révolution au sens noble de leur islam. »

James Courtwright, “A Small Town in Ghana Erupted in Violence. Were Jihadists Fueling the Fight?” New Lines Magazine, 25 January 2023. An excerpt:

New Lines traveled to Bawku to investigate the conflict and found that, rather than creeping jihadism, residents, local politicians and community leaders described a dispute with deep historical and political roots being fueled by partisanship, social media and weapons proliferation. The war on terror may be on Ghana’s doorstep, but an eagerness to conflate local conflict with international jihadism may in fact only be fanning the flames further.

Wolfram Lacher, “Libya’s New Order,” New Left Review, 26 January 2023. Quoting:

Some might dismiss this episode [of fighting in Tripoli in August 2022] as yet another skirmish in an interminable conflict between the shifting armed alliances in Tripoli. And so it may be. But there is also a broader trend at work here. Over the years, these repeated confrontations have entrenched the power of several fearsome militias, which have become increasingly professionalized while gradually expanding their territory. Post-Qadhafi Libya offered exceptionally favourable conditions for such groups, most of which operate as official security forces and enjoy generous state funding. At first, these organizations were unruly, fractious and unambitious – prone to splits and petty internal rivalries. Yet over time they have developed centralized leadership structures and absorbed growing numbers of the former regime’s military and intelligence officers. The result has been the consolidation of a militia landscape that, in Tripoli alone, initially involved dozens of different armed groups.

Obi Anyadike, ” ‘Everyone knows somebody who has been kidnapped’: Inside Nigeria’s Banditry Epidemic,” The New Humanitarian, 30 January 2023. A key paragraph:

The most feared bandit leaders levy taxes, settle local disputes, and have praise songs sung about them. These are young men, typically in their 30s, casual in their use of violence, who claim a political solidarity with the pastoralists even though Fulani – like Ismael – are among their victims. When not feuding, they cooperate with one another in shifting alliances, but also compete in a perpetual arms race for deadlier military equipment.

Jared Miller, “The Politics and Profit of a Crisis: A Political Marketplace Analysis of the Humanitarian Crisis in Northeast Nigeria,” World Peace Foundation, 1 February 2023. An important section (p. 24):

Since the conflict began, more than $3.8 billion in international aid has flowed into the northeast. In 2020, UNOCHA estimated that $1.1 billion was needed to provide necessary humanitarian aid to an estimated 7.8 million people, 3.8 million of whom needed food security assistance. The diversion of humanitarian aid is not unique to Nigeria, but it has become part of the political economy of the northeast and has created vested interests in a continued crisis.

[…]

Humanitarian actors report immense pressure to shift the narrative, and the corresponding agenda, from humanitarian response to development despite the continued insecurity or lack of government control. This is a call that is shared by both the Nigerian government and Nigerians in the northeast, though their reasons are likely very different. Some sought a return to normal life while others may have seen it as an opportunity to use development rents to fund their political budgets. Regardless of the motivation, collective calls to shift to development also came with an input of funds for rebuilding.